A friend who went to St Xavier's College with me in

Kolkata thought, ‘good, bad or ugly’, India desperately needed a change. She wants to see

Narendra Modi’s ‘numerically emphatic victory’ as the causal effect of India’s

national aspiration for change. Now based in the US, I could see that she had

shed her sympathy for the Left, which was so common among college-going youths

of the 80s and 90s in Kolkata.

|

| The Left no longer stokes public imagination as it used to for years after Indian independence |

A Bangalore-based techie, who spent over five years

in school with me, openly aspired and vehemently argued for a Modi government at

the Centre. Surprised by the intensity of his argument and strength of his conviction,

I was tempted to ask how his father - a veteran journalist, writer with strong

Left leaning – felt about this change in stance within the family! My

friend wasn’t apologetic, instead he underlined the fact that “these are two

generations representing different times in history”.

Narratives like these are helpful in understanding

popular discourses which shape socio-political landscapes. It becomes all the

more interesting when viewed from a distance so as not to be overwhelmed by

proximity to the very moment in time and the object of analysis.

The decline of the Left is a fact of life not only

within the geographical confines of India but across the globe. However, that doesn’t in anyway imply the decimation of the voices of protest and dissent which are so closely related to the politico-philosophical

ideology of the Left. A friend once told me, “The official Left makes way for the multi-headed

heterodox Left.”

His words sounded paradoxical then, but being a

bystander to the global upheavals at multiple levels of society one can easily

infer that socio-historic perspectives do make a difference. Not that people

necessarily analyse and act, but circumstances make them think in a definite way.

The demise of the ‘nation state’ as a dominant discourse and the rise of

‘neo-liberalism’ as an economic doctrine played catalysts to the so called socio-historic

transformation and India is no different.

The weakening of the ‘nation state’ as a fall out of

the decline in Keynesianism has withered those institutions – like the public

sector, bodies upholding public and social consumption etc. - which projected

the dominance of ideologies that for years have been the hallmark of the Left

and trademark of the essence of the Congress.

There is no denying the fact that economic

liberalisation was initiated by a Congress government in 1991 and the process in

fact, had started even before, probably during the later years of Indira Gandhi

government in the early 80s, but we had been witness to an ongoing ideological

and emotional tussle between the socialistically-inclined segment of the Congress

and its liberalising counterpart. Whenever the party was in trouble it took no

time to swing back to its ‘ex-reform’ agenda.

Similar was the case with the Left. Apart from the

crises emanating from the electoral arithmetic since 2008, the Left was

virtually hitting its head on the wall as politics as a manifestation of strong

ideological and moral compulsion took a backseat following the emergence of

‘neo-liberalism’ as a dominant doctrine.

|

| Mamata Banerjee and her Trinamool Congress party decimated the Left in its bastion |

If globalisation contributed to expansive

capitalism, neo-liberalism as a doctrine single-handedly ensured that politics

was no longer string-tied to ideology and became a function of ‘service

provision and clientelism’. The symptoms were evident in West Bengal, once the

citadel of the Left. The old war horses and foot soldiers of an ideology,

many of whom spent their whole lives dreaming of and aspiring to bring about

social change were replaced by clients or beneficiaries of such a long Left

regime. These elements - heterogeneously composed of promoters, primary school

teachers, owners of rice mills and brick kilns, small traders etc. - backed

successive Left governments to ensure nothing but self-interests. That they are

not tied to any ideological or moral baggage is evident from the fact that some

of these elements quickly changed camps since the inauguration of a new Trinamool

Congress government.

The failure of the Left was not necessarily because

it allowed itself to be swamped by opportunists and hoodlums – which come with

any government, but for its failure to recognise that the lexicon of the

dominant political discourse had changed. Even when it recognised what was

lacking, the Left leadership failed to capitalise because of a short span of

time and they were not convinced whether their corrective course of action was

in right direction. Hence the party apparatus and the electorate were not

readied for a paradigm shift in policy and thinking.

The euphoria of being in power for such a long time

in Bengal, actually resulted in a sense of complacency, restraining an already

dogmatic Left leadership to peep out of the window and see for themselves how

the world had changed, even though it was palpable to those who moved out of

the geographical confines of Bengal.

The stimulants of change were in the air, as some

medical practitioner would refer to here in the West in case a patient was

suffering from flu (popularly known as Influenza in India), but the Left

leadership failed to acknowledge them. Instead, they continued to harp on ‘old

politics’ - characterised by stoking fear and insecurity, treating people as faceless numbers - as depicted

in their voter identity cards, denying the minimum dignity that a person is

entitled to, and sermonising the electorate rather than interacting with them

with due respect to their level of

knowledge and enlightenment.

In fact, during the just concluded parliamentary

elections, the strategy of the Left in West Bengal was confined to ‘negativism’

- based on their hope to encash on splitting of votes between the Trinamool

Congress, Congress and the BJP – and ‘hopeless campaign’ which relied more on

ridiculing political opponents rather than putting forward a ‘sense of hope’ - pre-dominant

in a neo-liberal set up as it empathised with individualism.

What then happens to the organic relationship that exists between

the Left and voices of dissent ?

|

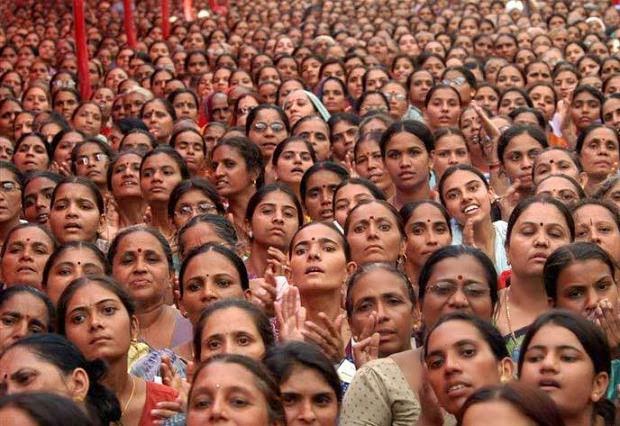

| Social movements now play a crucial role in airing voices of dissent |

No one expects the dissenting voices to subside with

the decline of the mainstream parties to the Left of India’s political

spectrum. More than anything else, the social movements and in some cases the

civil society organisations are playing the role of the Left. Not that there is

complete coherence in their policies and courses of actions, but some sort of

rhizomic (ginger-like, i.e. if one cuts a slice of ginger and plants it, the

slice grows like an independent rhizome but with all the traits of the mother

ginger plant) relationship exists between various social movements.

The Aam

Aadmi Party is a classic example as to how civil society organisations can

outgrow themselves from being the intermediaries between the state and the individual

to emerge as independent political formations, performing the role of the ‘social Left’. Moreover, some political figures like Mamata

Banerjee and Nitish Kumar will try to play the ‘moral Left’ leave aside the

various radical, non-state Left actors like the Maoists.

It's not the prerogative of an analyst or an observer to speculate the future, but all said and done, it seems that probably the institutional Left has exhausted its role in Indian polity.

A version of this article is published in the Financial Chronicle: "Left is dead, long live the Left"

A version of this article is published in the Financial Chronicle: "Left is dead, long live the Left"

Tirthankar Bandyopadhyay is a journalist and media consultant.

He can be contacted at tirthankarb@hotmail.com Twitter handle: @tirthankarb

All comments are personal.